01 - 02 - 2024

Written by BPTW Associate, Alessandro Chiola

Walking through London, it is possible to establish when a building has been designed and built. Fashions or regulations from a particular time often dictate the materials, colours, balconies and glazing on a façade. In the past 13 years, many discussions about density, typology, tenure, and safety have culminated in regulatory evolution. From the London Housing Design Guide in 2010 which bore the brick aesthetic of the New London Vernacular to the GLA’s Housing Design Standards, new regulations continue to improve quality, sustainability, placemaking and safety, but few have had as much impact as the 2022 Building Safety Act (BSA). In this article, BPTW Architectural Associate Alessandro Chiola establishes design solutions for the BSA’s Second Staircase regulation and considers its impact on the future of London’s residential aesthetic.

A necessary regulation shrouded in uncertainty

The Building Safety Act is the most important regulation of recent years. The Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) introduced the Act in response to the tragic Grenfell Tower fire and to prescribe fire safety in residential buildings. Successive Government alterations and an absence of formal documentation have brought uncertainty and lack of clarity in design decision-making.

The latest announcements from the Government created shockwaves across the construction industry by detailing the requirement for a second staircase in high-rise residential buildings comprising first, in all buildings over 30 metres and second, in all buildings over 18 meters. Built environment professionals have interpreted this to mean a second core with a protected lobby will be required, including a staircase and at least one lift. These amendments continue to affect many London-based residential schemes in the pre-planning and technical stages, where projects have stalled or undergone redesign to anticipate and seek to comply with the new regulation.

An architectural perspective

Architects are responsible for interpreting the spatial implications of this changing regulatory landscape. They must understand how every residential typology can respond appropriately and how it will alter the future lives of those living in the new buildings. As an Associate at BPTW, I have seen large residential projects, masterplans and regeneration schemes impacted by the second staircase. I have experienced clients’ and fire engineers’ varied approaches to addressing it, where some have proceeded with caution, believing that a second pair of additional lifts will be required, and others have instructed redesigns to accommodate one additional stair and lift.

Whatever the approach, the New London Vernacular established over the last decade is evolving. The regulation will impact every residential building’s form, massing, and scale. How will London’s urban landscape transform, and can it be predicted?

Exploring the impact on ‘Tall Building’ typologies

The following section will explore spatial implications on a number of common building typologies which, under the new GLA guidance and Building Safety legislation definitions, could be defined as ‘Tall Buildings’ ie buildings that we commonly see over 18m (albeit many of these are typically and have historically been considered as mid-rise typologies).

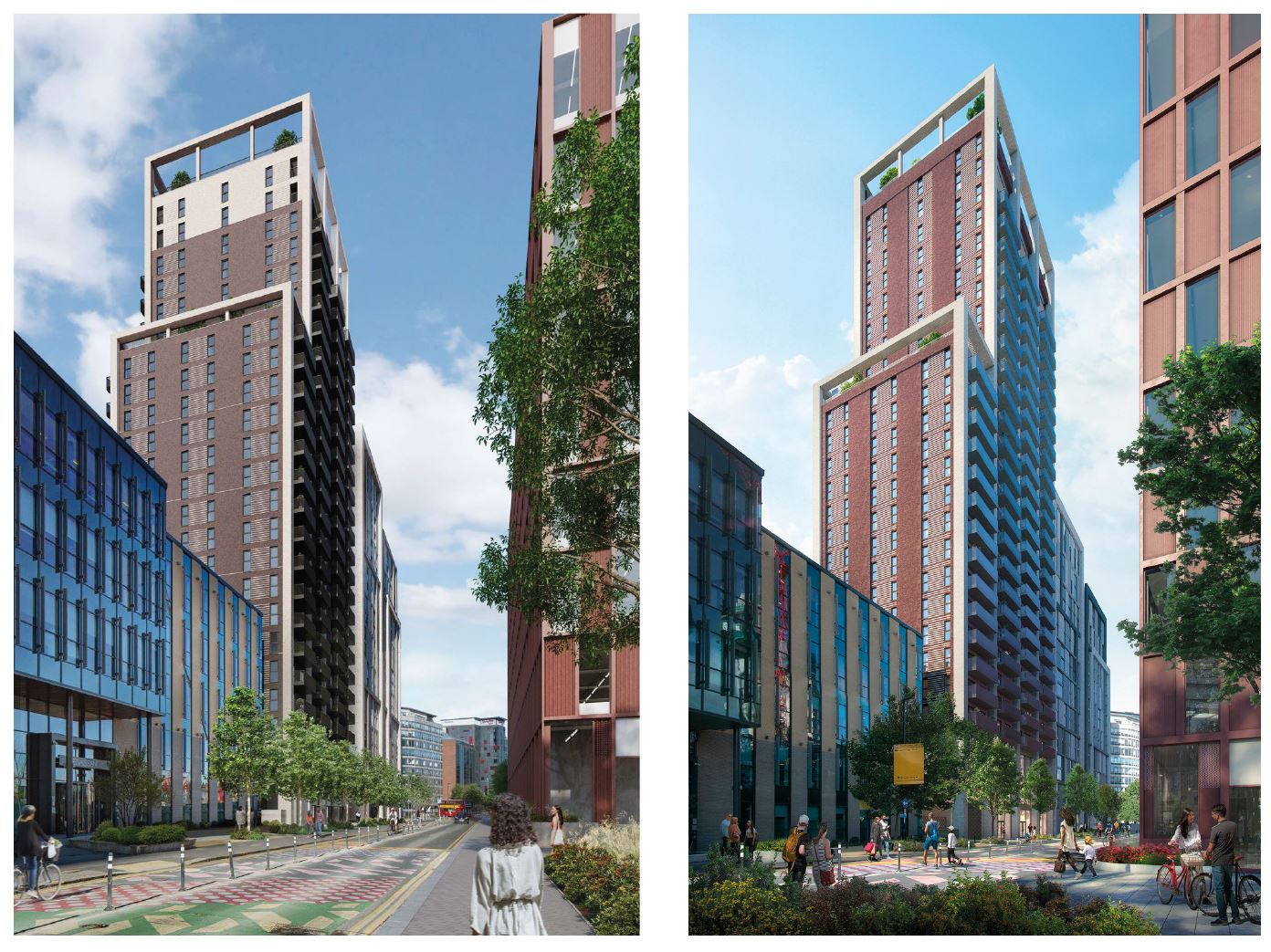

1. Towers

Modern buildings over 30 metres (10 storeys) are more often than not towers, typically narrower and more slender in form, recognisable from their efficient arrangement of one central core and radiating apartments. From Stratford and Canada Water to Elephant and Castle, towers are a primary feature of new developments constructed across London.

It is not spatially challenging to add a second core to a tower, and many tall buildings in Europe have two cores. However, a building’s efficiency will be affected, and each additional core will increase the circulation space. More apartments will be required per floor to improve efficiency as a result.

Nevertheless, an additional core will impact a building’s shape and mass with fewer options for the slender form created by setbacks or terraces on the upper floors. To counteract this, architects can seek design solutions that integrate a tower into the city’s fabric. For instance, improving the quality of place at street level.

2. Deck access blocks

Linear blocks are a familiar sight on London’s skyline. A popular postwar housing typology, the then-new designs brought open space to the upper floors and offered respite from the car-dominated streets below. Its success was short-lived, and many of these buildings have been demolished, like Robin Hood Gardens in Poplar.

While a linear deck-access building might appear relentless and slab-like at 30 metres tall, it can work well in a ‘mid-rise’ scheme. Introducing a second core may be easily achievable. However, there will be fewer opportunities to reduce the massing on the upper floors which continues to make this typology less suited for taller buildings. On the other hand, residents will walk shorter distances to their front doors, and the design of access decks will be less restricted because of the two entries.

3. Double-banked block

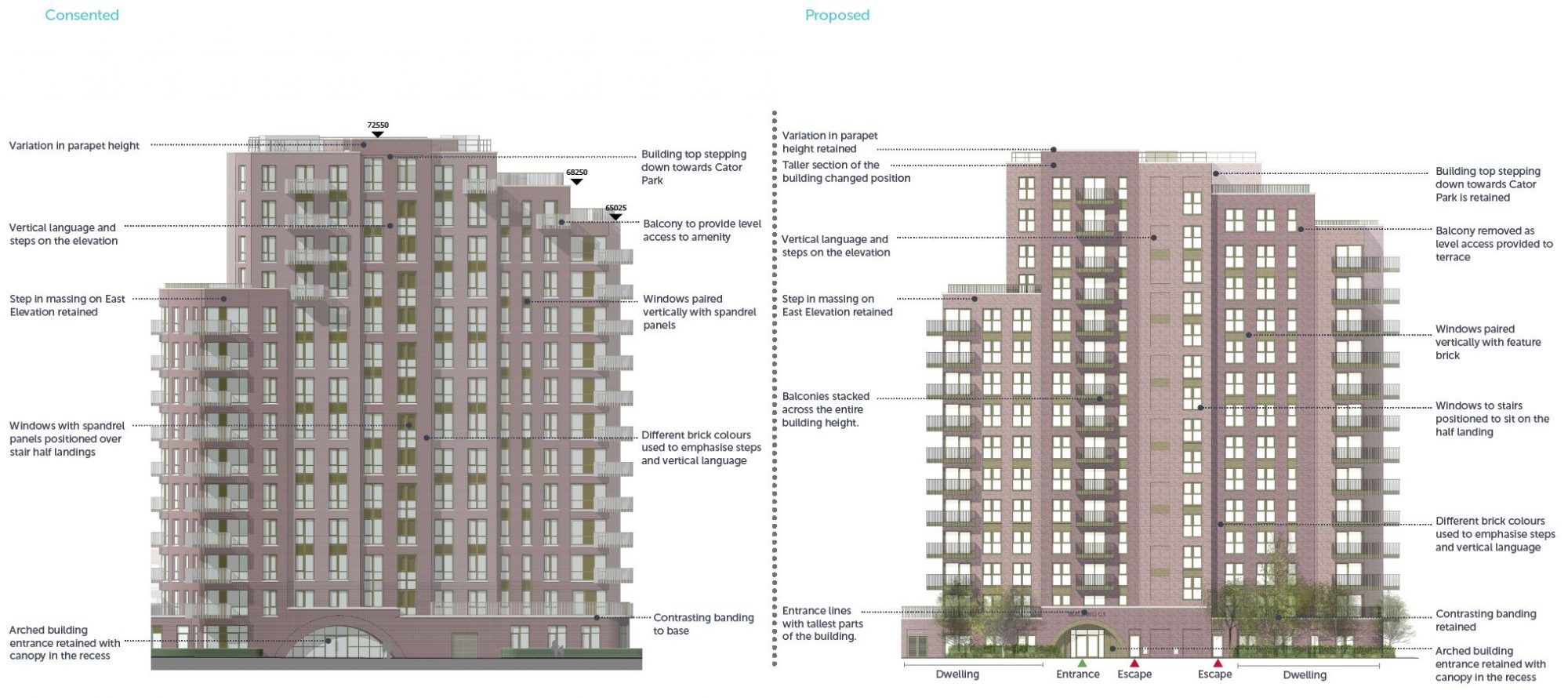

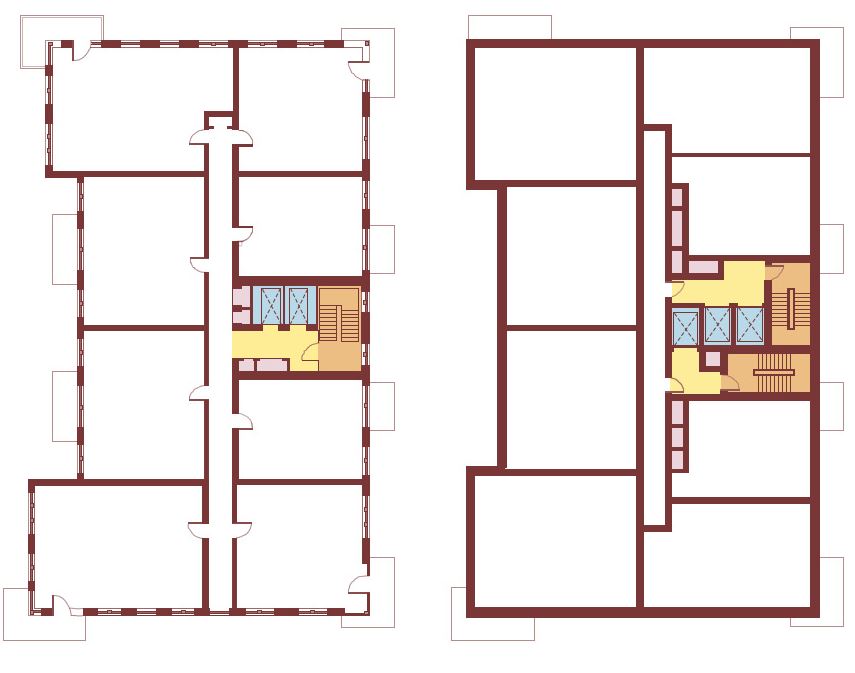

Double-banked linear blocks are one of the most common residential building typologies today, offering design efficiency with up to eight apartments per core. Integrating the second staircase into this typology could be achieved by either centrally locating the core or positioning it at opposite ends of the communal corridor.

The large area created by the new, two-core arrangement will reduce the building’s efficiency, and more apartments will be needed to balance finances, resulting in a bigger footprint and mass. Furthermore, a second staircase makes it harder to articulate the upper floors to lighten mass and scale, especially if the cores are apart. The design enhancements to improve a building’s form and slenderness could result in an inefficient layout, with 50% of the floorplate occupied by the cores on upper floors. Finally, increasing the number of apartments on each floor plate will reduce the number of dual-aspect homes, making it harder to achieve other design requirements like ventilation.

4. Podium blocks

The podium typology is shaping many new neighbourhoods across London, and its popularity is a result of its flexibility. Podium blocks provide opportunities for multiple building types and heights together, enable separate public and private spaces, and offer space for commercial units with active frontages and ancillary plant spaces at ground level.

Tall buildings linked by a well-designed podium can have different footprints but must provide adequate separation distance between buildings.

Introducing a second core is likely to create a larger footprint. If the site can accommodate the extra massing without compromising overlooking and overshadowing, then the typology might still prove valid. Architect’s well-established techniques of massing erosion (such as set back top floors) can overcome these issues, but buildings with smaller footprints (five to six homes per floor) will face efficiency issues. New circulation space configurations and mass erosion to improve a building’s slenderness may unexpectedly expose cores and create blank facades due to the new core configuration.

Buildings Over 18 metres but below 30 meters

The prevailing height across central London is six to eight storeys. These buildings are commonly seen in the typologies explored above – Deck Access Blocks, Double-Banked Blocks and Podium Blocks. They often mitigate the scale of new development and create a positive relationship with the context. However, moving forward there will undoubtedly be a substantial difference between six and eight storeys in the following ways:

- Building form: Buildings over 18 metres will now have bulkier massing and larger footprints. There will be fewer opportunities to create a transition from the base to the top because the core will occupy a larger portion of the floorplan.

- Efficiency: Seven to ten-storey buildings will be much less desirable from a development and particularly a viability perspective, because the extra space and cost required for the second core will be considerable. Additional homes (and height) will likely subsidise the increase.

- Affordable homes: Service charges will increase because of the additional lifts, making affordable buildings over 18 metres less desirable. The knock-on effect could have some positive aspects; In my experience, I have found that residents in affordable homes prefer lower buildings, are mindful of high service charges, and want to build a community with their neighbours with easy access to communal amenity spaces. However, the ultimate impact could be that it is harder to meet the demand for affordable homes. Ultimately, different residential typologies could become more appropriate for different tenure types.

Architecture in Tomorrow’s London

Clear guidance on the implementation of the second staircase is yet to be published, but Councils and the GLA already require updated designs for all buildings over 18 metres. Architects are testing different core arrangements and building typologies to understand the implications and realise the immense spatial impact of the policy on most new residential buildings in London. Mid- and low-rise typologies will be the most impacted, and we risk seeing seven to ten-storey buildings disappearing altogether as housing developers either seek to remain under the threshold, or push to build ‘Towers’ to negate cost and viability considerations. London’s apartment buildings will get taller, bulkier, have larger footprints, and have less variation in top-floor massing. As we consider our work as an industry going forward, it will be important to reflect on the potential impact of this regulation on building typology and height across London, and other urban areas.

Cities have always been built in stratification, and a 19th, 20th or 21st-century building is immediately recognisable by its appearance – an appearance that is often the product of different regulations, societal needs, new materials, and inventions in building techniques. Building regulations play an ever-increasing role in the appearance of today’s buildings, but their residual impact on “design” is rarely considered.

What will it be like to walk through London in the future? Will we find ourselves among a forest of similar-looking buildings designed because of rigid regulations that have made it more challenging to respond to the identity and character of a place? Whilst undoubtedly this regulation is a very necessary step towards safer buildings which is the most fundamental thing to consider, we need to ensure we also consider how the policy may impact other aspects of design, quality of place and townscape. New buildings will be much safer because of the Building Safety Act, but we must ensure, as built environment professionals, that quality, character, and identity are not lost in the process.

Alessandro Chiola is an Associate at BPTW, where he oversees a design team working across all RIBA stages on a number of urban residential-led regeneration and masterplanning schemes. He is a member of BPTW’s strategic ‘Spatial Principles’ group which works across the practice to pursue best practice in relation to the spatial arrangement of our schemes – at an urban, site, building and dwelling scale. He is also involved in the practices’ ‘Design Review’ group which seeks to ensure, through a regular design review process, that BPTW’s schemes integrate high quality design principles, placemaking approaches, and regulatory standards from the outset.

Useful Further Links

BPTW’s previous bulletin on the requirement for second staircases in residential buildings over 18m: