02 - 09 - 2022

Written by BPTW Head of Business Development, Israel George.

Amidst a rapidly changing social landscape in the UK driven by the pandemic recovery and a cost-of-living crisis, social value is a vital part of the design and procurement of buildings. While this has the potential to bring great societal benefits, there is still uncertainty around how architects and other built environment professionals can deliver meaningful social value. With this in mind, BPTW’s Head of Business Development Israel George discusses the opportunities and hurdles faced when delivering social value on projects. He looks at how, in particular, architects should be focused on placing social value where it is most needed – at the heart of good design.

Since the 2012 Social Value Act (1) and subsequent Procurement Policy Note (2) and the Construction Playbook (3) in 2020, social value has become critical to public projects – and rightly so. Including it in the procurement of design consultancy services allows immaterial social factors, like improved wellbeing or better life prospects, to become influencing factors in a built environment project alongside more traditional considerations, such as financial viability (4). This cultural shift allows clients and building professionals to do more with their resources and contribute to buildings and places that actively improve society. However, the industry is still uncertain about how best to define, plan, deliver and monitor social value (5).

Understanding social value in the built environment

In 2021, the UK Green Building Council (GBC) published a Framework for Defining Social Value. The document provides professionals with a step-by-step process for delivering social value on any built environment project alongside best practice principles (6), ensuring that community needs are central to development. Written by a Social Value Task Group of industry stakeholders, the framework responds to the absence of a specific industry definition of social value and a flexible delivery process (6). As a result, GBC’s framework provides a workable, motivating definition of social value that could become the much-needed industry standard:

…. social value is created when buildings, places, and infrastructure support environmental, economic, and social wellbeing, and in doing so, improve the quality of life of people.

UKGBC’s Framework for Defining Social Value 2021.

Such a definition will inspire architects and built environment professionals because it recognises the influence of the built environment on people’s lives and encourages us to imagine a better future through design.

As social value has gained traction in the procurement and delivery of public sector projects, a need to capture tangible social value outcomes has emerged. A variety of measuring systems have been developed to achieve this and each brings its unique focus on what social value is – from HACT’s Social Value Bank and the RIBA’s Social Value Toolkit for Architecture to the National Themes, Outcomes and Measures (TOMs) Framework. In conjunction, social value outcomes are typically monetised using the Social Return on Investment measurement (8) to allow them to feature in economic models and provide an equal basis for comparison with other decision-making factors.

While it may initially seem reductive to consider social benefit in pounds and pence, it provides architects and built environment professionals with a fantastic opportunity to express the value of their actions (7). Yet, the inclusion of social value in procurement and the different measuring processes available means they can also face a complex array of additional responsibilities on top of their traditional responsibilities. Therefore, it is important to reflect on how built environment professionals adapt to these opportunities and constraints to maximise the benefits of excellent design.

Social value ambitions

As a socially focused architectural practice, BPTW is committed to delivering social value in and beyond our appointments. This has been at the core of our practice culture since our earliest community-led work in the nineties and is reflected in our long-established CSR commitments like regular financial donations to charities and community projects. Following recent milestones in UK social value legislation, we have expanded our social value activities into a comprehensive programme linked to our wider concerns in education, employment, equality, diversity, and inclusion. We now offer a structured Careers in the Built Environment programme to schools and colleges, and we frequently deliver social value activities that benefit from our architectural expertise, such as pro-bono design services and advice sessions.

Like others in the industry, this growing responsibility for social value has required a unique design approach. We have spoken with clients about their social aspirations and abilities, built relationships with community members and, ultimately, learned to deliver meaningful place-based social value initiatives, all the while navigating the challenges and benefits this brings SMEs like us. We see enormous potential in this work and are keen to translate our ambition and social outlook into viable and meaningful initiatives that bring long-term value to people and communities. However, our experience of social value delivery in architectural design has raised three discussion topics that require resolution for the concept to thrive:

- How is social value affected by procurement processes?

- How can we best deliver social value initiatives?

- How can we accurately measure the value of our actions?

In the following section, we discuss the nuances of these topics and address the common issues faced with suggestions for clients and professionals.

Social value in procurement

UK public procurement legislation requires the evaluation of social value in all central government procurement with a minimum weighting of 10% allocated to social value, stressing that social value must be a differentiating factor in bid evaluation (3). As a result, architects and built environment professionals will be familiar with developing social value propositions when tendering. However, shortfalls in tender requirements, few requests for actionable social value plans, and the absence of a unilateral definition and methodology have created a void between bid writing and the delivery of social value actions. Additionally, the measuring processes in place often have a greater affinity with the construction phase than the design process (7). These issues can create uncertainty amongst bidding SMEs when balancing a tender-winning response, a meaningful social value plan, and delivery capabilities.

Discussion points

Clients’ preferences for defining, delivering, and measuring social value vary. This can impact the consistency of an SME’s social value approach.

While a universal definition for social value remains in debate, the greatest tool design consultants have in social value delivery is partnership working. When a client does not have an agenda, agreeing on a social value definition and priorities at the start of a project can help eliminate ambiguity and allow the consultants to identify a clear route for delivery. Writing a Social Value Brief and reviewing it regularly can provide clarity for the design team and client alike while offering a mechanism to update the social value requirements in response to stakeholder engagement (9).

Articulating a vision for social value early on can help the client and consultants to work together and develop place-based social value actions linked to community needs. For the Teviot Estate Regeneration in Poplar, BPTW and our partner Delvendahl Martin committed early on to a ‘Community Design Fund’ that offers pro-bono design services for projects selected by the community. Our actions have supported local festivals and the improvement of community facilities, such as our proposal to design a new community pontoon in the Limehouse Cut canal. By designing this meanwhile use, BPTW and Delvendahl Martin are building relationships with residents that have benefited from the wider regeneration while creating an enjoyable community space.

The methods selected by clients to assess social value in bids are often more relevant to contractors than other construction professionals.

This is a well-recognised hindrance to design professionals when bidding for public projects (5). On occasions, we have seen unreasonable social value expectations for architects, such as the provision of construction training cards which contractors can provide with ease. In response, industry bodies like the RIBA and HACT have developed measuring tools such as post-occupancy evaluations that emphasise the social value of the product – the building or the place (7). In these instances, built environment consultants can call for clients to use standards better suited to their professions. The continued uptake of these tools will encourage the quantification of social value in terms of wellbeing and life satisfaction generated by outstanding design as well as traditional measures like job creation.

Recognising the inherent benefit of superior design and providing mechanisms for quantifying this brings additional industry benefits because it allows designers to monitor the success of their actions and implement improvements for the future. In its Social Value Toolkit, the RIBA states that the introduction of post-occupancy evaluations and social return on investment will provide the data needed for architects to concretely demonstrate the benefit of their work and drive forward improvements in design quality (7).

Can the constraints of the bidding process jeopardise the selection of a social value proposal that best meets the project’s unique requirements?

In the absence of further changes to the project bidding process, we must make the best of the existing system. Clients and partner organisations should ultimately want deliverable and appropriate proposals. To achieve this, there must be an onus on clients to make local needs for social value clear in the tender documents and to establish fair marking criteria that truly consider community benefit. However, in the absence of this information, researching a client or particular local authority’s goals and existing social value programmes can help built environment professionals create targeted, well-justified social value initiatives without excessive resource requirements in delivery. Importantly, an immediate review of the social value proposal upon appointment can help tailor it to the client’s and community’s needs, thereby ensuring the best use of the consultant’s commitments and resources.

Research at the tender stage can help bidders identify a client’s social value priorities and develop a suitable social value proposal. For Hammersmith and Fulham Council, BPTW proposed work experience opportunities in line with the council’s aspirations while also highlighting that the geographical distance between the beneficiaries and BPTW’s Greenwich studio made this opportunity inaccessible for many people. To address this, BPTW made a separate financial donation to cover transport costs for attendees. Additionally, we proposed an initiative focused on improving digital access. By building a relationship with the charity Ready Tech Go, we were able to support their Tech4Kids project with a financial donation to purchase laptops for children in the borough. Recognition of the client’s social goals and the wider economic picture helped us deliver a social value initiative with real benefit.

Delivering social value initiatives

Construction industry professionals are required to deliver social value initiatives as part of their project work, including on smaller projects. The planning and delivery of these initiatives are time-consuming activities. Additionally, the goals and aspirations of both the client and consultant may outstrip the resources available on the ground. One saving grace is that increasing our experience will contribute to better quality initiatives and more efficient processes, as long as an effective feedback strategy between clients, partners and beneficiaries is maintained.

Discussion points

Social value initiatives take a long time to establish, and their resource-intensive management can take staff away from fee-earning work.

Ideally, a project’s social value agenda would be determined before consultant appointment, allowing bidders to propose appropriate social value commitments that align with their expertise and resources, and can begin immediately upon appointment. This would help prevent social value commitments from overrunning a project’s completion – a risk on smaller projects. When design consultants are responsible for planning and managing social value initiatives, partnership working and honesty with clients about resourcing can help balance deliverable initiatives with meaningful outcomes. Monitoring the time spent on initiatives also helps predict and control resourcing on future projects. Additionally, as methodologies from the RIBA and HACT become widespread, design professionals like architects can deliver social value through their professional services and expertise (7), thereby easing resourcing requirements while delivering greater value.

Good quality social value initiatives benefit from strong relationships between partner organisations, the client and the community, and the consultant. Forming these relationships can be challenging, especially for SMEs working outside their locality or without pre-existing contacts.

Encouraging clients to take the lead and harnessing their existing network can help connect professionals with the right partnership organisations and beneficiaries quickly. Therefore, providing more time to design and deliver the initiatives. Alternatively, embedding social value into everyday business can extend our social value network (10). As professionals, we have a well-developed network of contacts, even if they are not related to “social value”. These existing relationships can be the starting point for identifying new contacts relevant to the project or community.

“The two weeks I spent with BPTW have given me great insight into the world of architecture and what it entails. Being able to work with software that I had never used before such as Photoshop, AutoCAD and Sketchup was truly amazing. Overall, it was a brilliant experience working alongside my mentor Paul Daramola and the team at BPTW.”

Pictured: Joshua Braithwaite from LSEC alongside BPTW mentor Paul Daramola

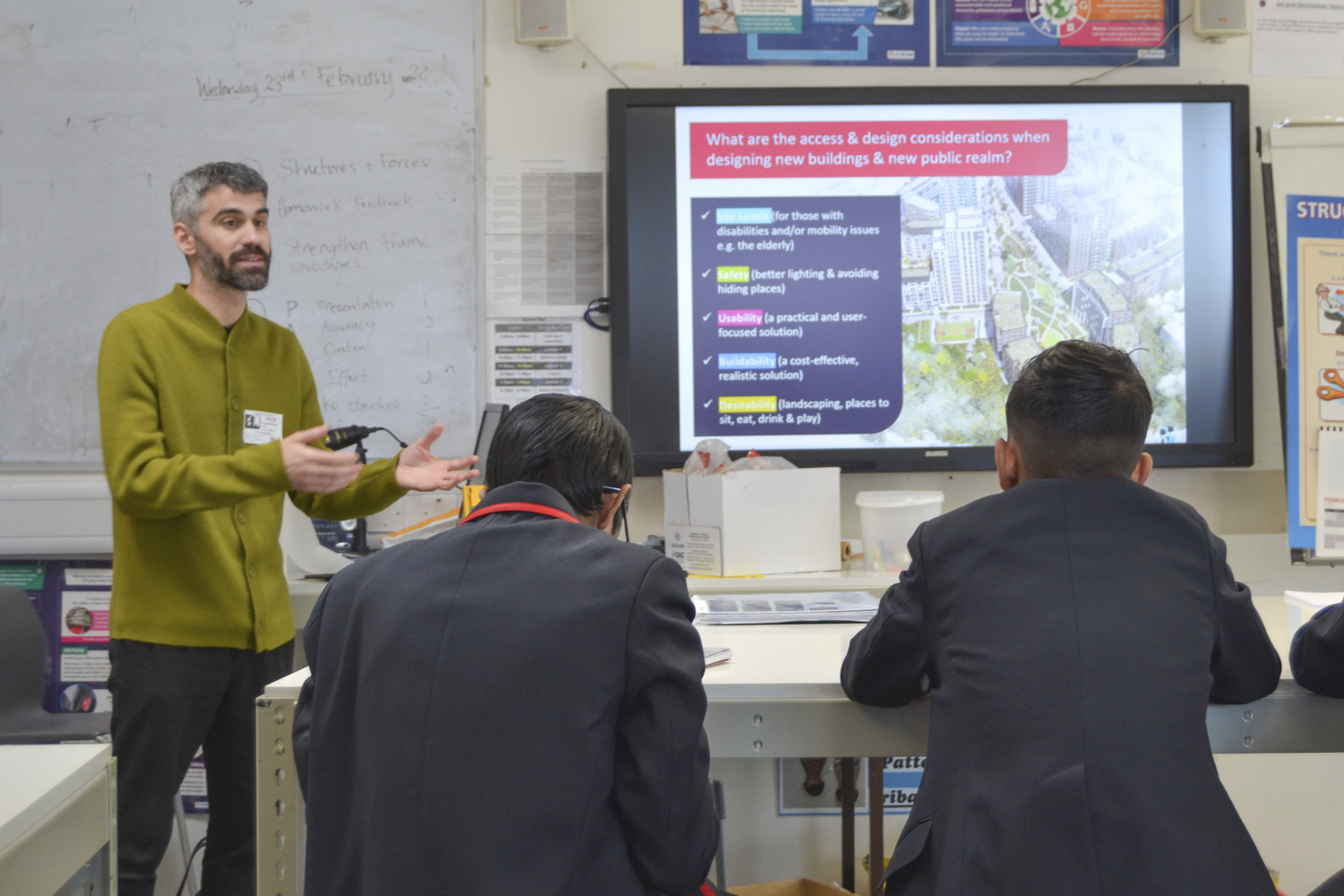

An all-encompassing social value strategy is a major component of Poplar HARCA and Hill’s transformational Teviot Estate regeneration and BPTW has created a strong partnership with both organisations to support their goals. Poplar HARCA indicated a desire to improve social mobility through quality industry-education partnerships early on. Using the client’s existing relationships as a springboard, BPTW is collaborating with local schools, Leaders in Community’s Be Inspired programme and Hill’s Teviot Talent Pool to deliver careers talks, mentoring and work experience – all activities we have developed through our Careers in the Built Environment programme.

Natalie Gray, Leader of Art and Technology at Langdon Park School, on workshops BPTW ran for Year 7s and 9s as part of our Teviot Estate social value programme

Measuring value

There is no commonly accepted methodology for measuring social value success and, often, the consultant does not have a say in the chosen measuring process (5). While important in recognising the social benefits created by development, the measuring and reporting processes available can be onerous and resource-heavy, especially for SMEs without dedicated social value staff. Finally, contractual responsibilities for delivering social value should be fair and appropriate. They should avoid contracts tied to immaterial social value outcomes (e.g., increased wellbeing) that can create undeliverable responsibilities and increased contractual risk for SMEs (an issue BPTW have contested previously on a contract). Instead, they can focus on quantifiable delivery commitments (e.g., those based on time and money) that can be well planned and managed by SMEs.

Discussion point

The newness of social value can create uncertainty when agreeing on contractual terms for social value delivery, especially in scenarios where social value has not previously been part of a contract.

Understanding and assessing the appointment to make sure your social value responsibilities are deliverable is vital. Particularly, when agreeing on how the ‘social value’ derived from your actions is measured and how any shortfalls in value may need to be repaid. The accurate recording of all resources and costs associated with social value activities is a critical part of this.

Recording and evidencing outcomes are time-consuming processes that further increase the resources required for social value projects.

Recording and evidencing social value outcomes benefit from both robust data collection processes and experience. While it takes time to establish the necessary recording processes, it is possible to use them as opportunities to improve the effectiveness of social value initiatives and enhance building design generally (7). Maintaining an appropriate balance between the types of data recorded with frequent measuring is also important when understanding success and improvement, particularly for area-wide regeneration or multi-phase projects. Quantitative data like reports and case studies can describe the success of an initiative from an individual perspective whereas qualitative data identifies overarching trends and can place any personal feedback into a wider context, both contributing to an enhanced understanding of social value delivery (9).

For the Teviot Estate regeneration, BPTW is supporting a far-reaching social value programme. To manage our contractual commitments, we created an effective social value monitoring system with Hill’s social value representative. This included proposals for each activity, monthly review meetings, progress and completion reports with evidence, a change management process, structured time sheets, and a running spreadsheet recording outcomes. By using this structured system, we have evolved our social value offer in response to community needs while continuing to demonstrate contract delivery. For instance, by seeking formal client agreement in advance, we redirected funding previously allocated to digital inclusion towards community centre renovations in response to conversations with community leaders.

The centre looks great, we’re really happy with the outcome. Thank you so much to BPTW for funding the redecorations!

Syed, Head of Charity at the Teviot Centre

Takeaways

During this discussion, several key themes emerged time and again that offer insight into how we can provide better, more sustainable social value for communities and businesses:

- Information and research – Better information from clients about local needs and opportunities, as well as the provision of details for beneficiaries and local partner and community contacts, will inform stronger and more cohesive social value plans across their supply chain. In the absence of this information, professionals can undertake research into local need, potential beneficiaries and partners, identifying relevant local initiatives to inform targeted and relevant social value proposals. These can be refined and agreed upon when the project commences.

- Relevance – Clients should seek to drive social value commitments and actions from their consultants that are most relevant to the nature of the organisation. This includes considering factors such as the scale of the business, geography and particular specialisms; in the case of architecture, suitable activities could include pro-bono design work and advice for community projects.

- Partnership – The greatest social value is created when people work together. Collaborate with clients and other consultants early to define social value priorities and agree on preferred measuring processes. It is possible to build a strong social value network by encouraging clients and consultants to share their contacts.

- Encourage – Built environment professionals should feel empowered to call on clients to present clear social value aims and methods at both the tender and delivery stage. Well-established priorities from the start will contribute to better quality social value initiatives and outcomes and also create a level playing field between applicants when tendering.

- Ownership – Dedicated individuals to coordinate the social value delivery process on the client and consultants’ side will ensure clear lines of communication, a consistency of approach and efficiency in the social value delivery process. It will also support the building of strong longer-term relationships with beneficiaries and local communities.

- Formulate – Clients and consultants should work together to develop robust briefing, planning, recording, measuring, and reporting tools for social value initiatives early on, such as a Social Value Brief, and undertake the same measuring processes multiple times during a project to understand the impact of their actions. This will bring extensive benefits when delivering social value initiatives as part of a contract, such as demonstrating the delivery of contractual responsibilities and generating the data needed to improve processes for the future. Thereby, creating better quality social value initiatives with effective resource and time management.

- Improvement – Sharing social value outcomes and experiences between clients and professionals and between peers can provide valuable insights and recommendations for developing better social value programmes. Additionally, data from social value assessments offer architects the opportunity to analyse the impact of their designs and understand how to improve them in the future.

- Inherent value – Emerging social value tools from the RIBA, HACT and other industry bodies emphasis the inherent social value of good design. Architects and build environment professionals can call on clients to use these standards that are better suited to their professions while encouraging a step change in how we understand design and social value.

As architects and built environment professionals, one of our greatest opportunities is to create better places in collaboration with the communities that use them. Whether through meanwhile uses, community events or training and work opportunities, social value offers us a pathway to identifying what communities really need, encourages us to commit to positive change, and helps us understand how things have improved and why. Designs centred on social value with established processes for measuring success and learning will go a long way in creating better homes, spaces and neighbourhoods, and in the end a more equitable society.

As Head of Business Development at BPTW, Israel George is responsible for creating and managing the implementation of BPTW’s business development and marketing plan, building client relationships, and chairing BPTW’s strategic business development group. He oversees the practice’s tender and bid processes and sits on BPTW’s Equality, Diversity and Inclusion steering group.

Endnotes

- Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012. Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2012/3/enacted

- Procurement Policy Note 06/20 – taking account of social value in the award of central government contracts, Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/procurement-policy-note-0620-taking-account-of-social-value-in-the-award-of-central-government-contracts

- The Construction Playbook. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-construction-playbook

- https://myice.ice.org.uk/ICEDevelopmentWebPortal/media/Documents/News/Blog/Social-Value-and-its-relation-to-SDGs-Simetrica-April-25-2019.pdf

- https://www.building.co.uk/focus/delivering-social-value-how-to-build-and-give-back/5103765.article

- UK Green Building Council’s Social Value Framework. Available at: https://www.ukgbc.org/ukgbc-work/framework-for-defining-social-value/

- The RIBA Social Value Toolkit. Available at: https://www.architecture.com/knowledge-and-resources/resources-landing-page/social-value-toolkit-for-architecture

- https://www.nefconsulting.com/training-capacity-building/resources-and-tools/sroi/#:~:text=Social%20Return%20on%20Investment%20(SROI)%20is%20an%20outcomes%2Dbased,economic%20value%20they%20are%20creating.

- Altered Estates 2. Available at: http://www.alteredestates.co.uk/

- https://www.ukconstructionmedia.co.uk/features/embedding-social-value-and-meeting-net-zero-goals/